First Impressions of the Fez Medina Jun. 2018

Originally reported for The View From Fez; June 13th, 2018, on my first tour around the Medina of Fez with one of its few female guides.

I’ve been fascinated with the idea of travelling to Morocco for nearly two-thirds of my life. When I started seriously researching and planning my trip, one of the first concepts that caught my interest was that of djinns – spirits of Arabic lore that help or hinder daily life.

The word djinn can also translate as “hidden from sight”, a meaning I couldn’t help but correlate to my initial wanderings of the famous Fez Medina.

Djinns were present in every zigzagging alleyway, threading their way around the people. They’re the padlocks on doors, the coloured streets with no names I’ll probably never be able to find again, the furtive glances from beneath hijabs and rounded eyes of the children holding their mothers’ hands, full of question.

They’re the subtle cues embedded in ancient architecture, the tricks of the tradespeople performed behind closed curtains, the many intricacies one will miss if they make the mistake of not looking up.

There’s a lot I could presume about Fez…and sense there’s more truth in what goes unsaid. In the space around what’s right before my eyes. In secrets I haven’t yet earned the right to hear. The kind of place you visit time and time again, only to realise you know less about it than when you started.

But still; I’ve got to try. So I enlisted the service of Fatima Zahra Hanafi, one of Fez’s precious few female tour guides. It was inspiring to be shown around the Medina by a female guide who turned out to be anything but reserved. Disarmingly confident, she immediately quizzed about my preferences and primary interests regarding Fez, and I felt reassured this would not be a typical assembly line tour.

“There’s a lot I could presume about Fez…and sense there’s more truth in what goes unsaid. The kind of place you visit time and time again, only to realise you know less about it than when you started.”

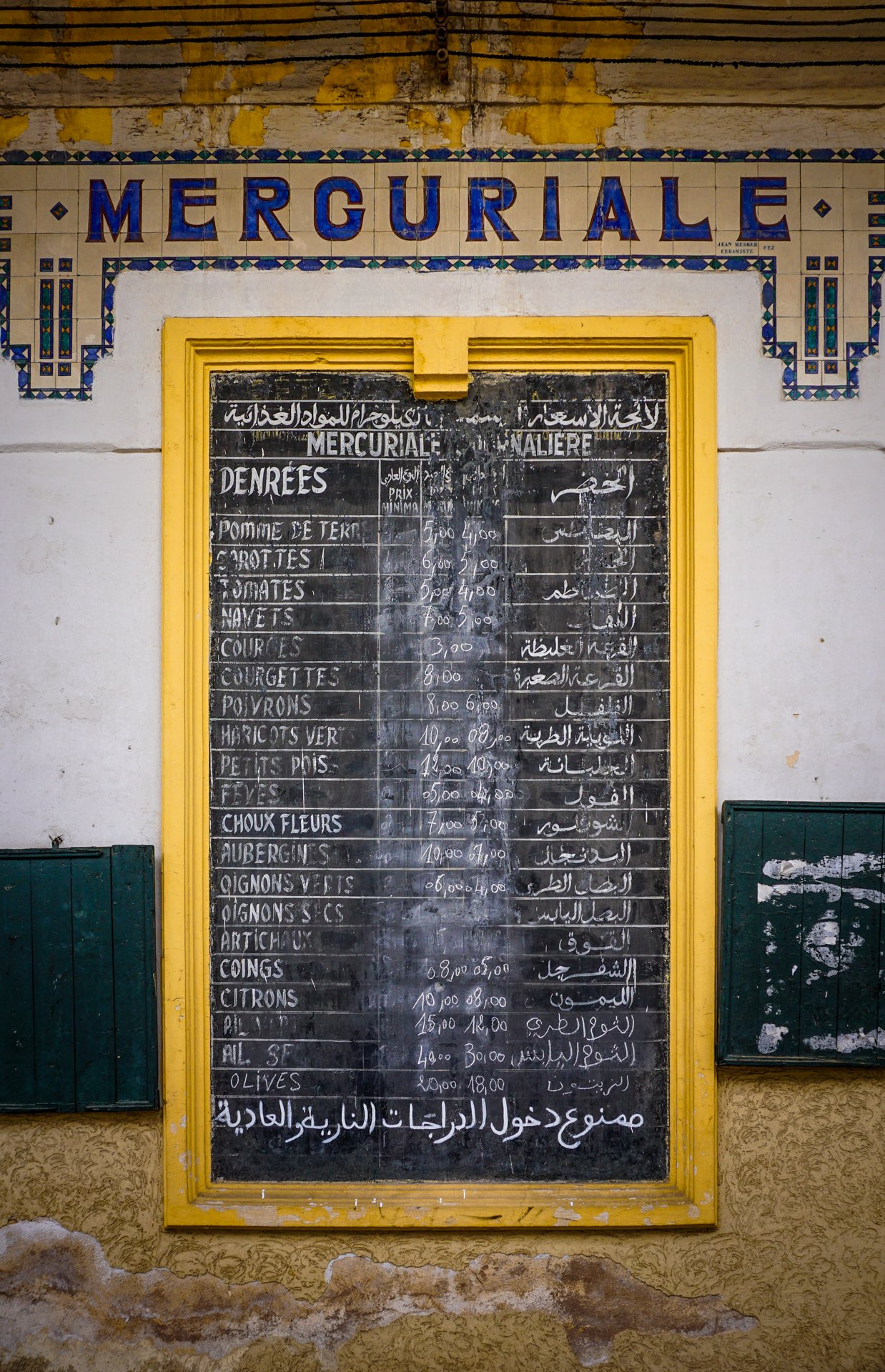

I should have expected no less for a city in which everything is handmade and meaningful. Nothing is superfluous. The cobalt shade adorning the zellij on the Blue Gate – signifying welcome. The protruding poles from the sides of minarets, which – to an outsider might represent shoddy construction – point in the direction of Mecca. The meandering lanes of shopfronts bursting with artisanal goods, an interactive exhibition of skill and legacy.

Many lanes house a particular trade with its own sensory hallmark. Fatima Zahra Hanafi steered me through them with casual dexterity and constant reminders to use my nose and ears. No sight, sound or scent went unappreciated. The musk of cedar from the woodworkers; the sour tang and brightly coloured puddles made by the dyers; the copper cacophony of metalworkers; the salty, pungent punch from the fishmongers. Filling in the gaps were crisscrossing tripwires of mint, leather, roasted nuts, caramelised sugar, and donkey droppings.

We wandered for hours, past herb carts and tottering horses and skittish cats and offerings of chewy nougat that wrapped around my molars. Fatima Zahra was rarely silent and always patient, encouraging my painstaking photography and pointing out fleeting details every few minutes that were invisible to my untrained eyes.

The travelling repairman with an iron in his hand. A low-set wooden barricade that begs passers-by to bow their heads in respect for Allah. Slots in the doors of mosques for inserting coins and asking God for forgiveness or good luck. An ancient clock in the side of a building, like a deconstructed sundial, that nobody knows how to read or how it once worked.

These obscurities lend just a little clarity to Fez’s mystery, and are what Fatima Zahra seemed determined to highlight alongside established crowd pleasers like the tanneries and carpet shops.

One such obscurity I’d researched ahead of time, and a detour she was happy to incorporate, was a look inside one of Fez’s bakehouses: communal ovens where families take their trays of dough and have sent back to them as perfectly cooked bread and biscuits.

The bakers – similar to the dabbawallas of Mumbai – have a well-oiled system that remains enigmatic to outsiders. They can tell, just by looking at the dough, which family sent it, and have it delivered back to the family’s house when they’re done. Of course, this system can never be shared, as I learned when I had Fatima Zahra try and find out for me. It’s a secret, she explained.

The bakehouses embody what is simultaneously enchanting and intimidating about Fez. They’ll lure you close with trays of tantalising goods, carried by exquisitely clad women. They’ll exhale hot, toasty plumes into the streets that stop you in your tracks. They’ll sometimes let you taste or take a picture of the magic – sometimes not.

But they’ll never reveal their secret formula.

I’m impressed by Fez’s strong virtues of community and devotion. I’m captivated with its inexplicable retention of time, ever present in the souks and centuries-old sandstone. I’m charmed by the few jovial local interactions I’ve had, facilitated by Fatima Zahra Hanafi – perhaps with those who’ve sensed I’m not a threat (or are willing to put up with my appalling French and Darija). And I’m looking forward to more. With time.

Inshallah.

“Many lanes house a particular trade with its own sensory hallmark. No sight, sound or scent went unappreciated.”